¶ Overview

(from Brook Schoenfield’s Threat Modelling Methods)

Threat modelling is an analysis technique often employed to identify the security needs of a system. As such, threat modelling is often undertaken while designing software and digital systems; threat modelling must be considered a foundational technique underlying system security, and in particular, secure design. Threat modelling is a key technique for system security’s associated development processes and strategies, the Security Development Life cycle (SDL) also called the Secure Software Development Lifecycle (S-SDLC).

Sometimes, systems are deployed without a threat model. In these cases, system stakeholders may choose to build a threat model post-release to identify any security weaknesses or un/under mitigated risks that are already in service.

In either case, the threat model’s output offers software makers a set of implementable improvements designed to improve the overall attack resilience and compromise survivability of the target system and its stakeholders.

Threat modelling can be defined as, “a technique to identify the attacks a system must resist and the defences that will bring the system to a desired defensive state[1].”

The definition highlights a few key points. First, threat modelling is not a design or an architecture, it is an analysis technique. Next, its purpose is to identify attacks and defences. Third, and this is key, the defences bring the system to its “desired defensive state.” That is, the object is not to bring the system to an ivory tower security perfection (which, of course, doesn’t actually exist in the real world, anyway).

In order to complete a threat model, one must first understand what defensive state a system’s stakeholders expect the system to achieve. To put that in a different way, a priori to analysing the attacks and specifying the defences, the analyst must understand against what the system must defend and to what level—what is commonly termed its ‘security posture.’… From the understanding of stakeholder risk tolerance, one may then derive the security posture of a system, its “desired defensive state”—that is, the appropriate defences that will resist those attacks against which the system and its stakeholders will defend.”

The primary output of a threat model undertaken as a software design activity must be a set of defences that taken together provide sufficient protection to the needs of the system’s stakeholders. Since risk tolerances and relevant threats are organizationally and system dependent, there is no “perfect” set of defences for every situation. Brook will base defence findings on industry best practices, as given by publications such as National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) security publications and/or customer standards and policies, as required.

Most threat model methodologies answer one or more of the following questions:

- What are we building?

- What can go wrong?

- What are we going to do about that?

- Did we do a good enough job?

|

.png) |

¶ Assets

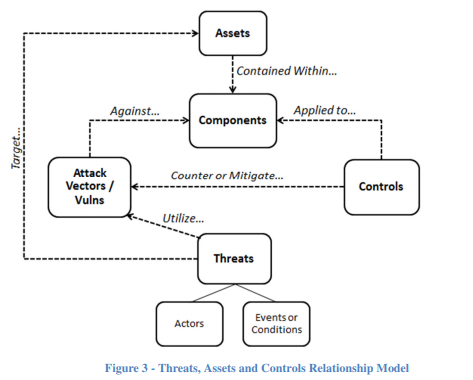

Job 1 for engineering-based security as described in NIST SP 800-160, is to determine what types of "assets" the organization desires to protect.

An asset is an item of value. There are many different types of assets. Assets are broadly categorized as either tangible or intangible. Tangible assets include physical items, such as hardware, computing platforms, other technology components, and humans. Intangible assets include firmware, software, capabilities, functions, data, services, trademarks, intellectual property, copyrights, patents, image, or reputation.

Within asset categories, assets can be further identified and described in terms of common asset classes.

NIST SP 800-160v1r1 Engineering Trustworthy Secure Systems November 2022 → 3.4 The Concept of Assets

Asset Class 1: Material Resources and Infrastructure

This asset class includes physical property (e.g., buildings, facilities, equipment) and physical resources (e.g., water, fuel). It also includes the physical and organizational structures/facilities (i.e., infrastructure) needed for an activity or the operation of an enterprise or society. An infrastructure may be comprised of assets in other classes.

Asset Class 2: System Capability

This asset class is the set of capabilities or services provided by the system. System capability is determined by (1) the nature of the system (e.g., entertainment, vehicular, medical, financial, industrial, or recreational) and (2) the use of the system to achieve mission or business objectives.

Asset Class 3: Human Resources

This asset class includes personnel who are part of the system and are directly or indirectly involved with or affected by the system. The consequences of loss associated with the system may significantly change the importance of this asset class.

Asset Class 4: Intellectual Property

This asset class includes technology, trade secrets, recipes, and other items that constitute an advantage over competitors. The advantage is domain-specific and may be referred to as a technological advantage, competitive advantage, or combative advantage.

Asset Class 5: Data and Information

This asset class includes data, information (aggregations of data), and all encodings and representations of data and information (e.g., digital, optical, audio, visual).

Asset Class 6: Derivative Non-Tangibles

This asset class is comprised of derivative, non-tangible assets, such as image, reputation, and trust. These assets are defined, assessed, and affected, positively and negatively, by the success or failure to provide adequate protection for assets in the other classes.

- NIST SP 800-160 Engineering Trustworthy Secure Systems https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/systems-security-engineering-project

- NIST SP 800-160 Vol. 2 Rev. 1 Developing Cyber-Resilient Systems: A Systems Security Engineering Approach

- NIST SP 800-160 Vol. 1 Rev. 1 Engineering Trustworthy Secure Systems

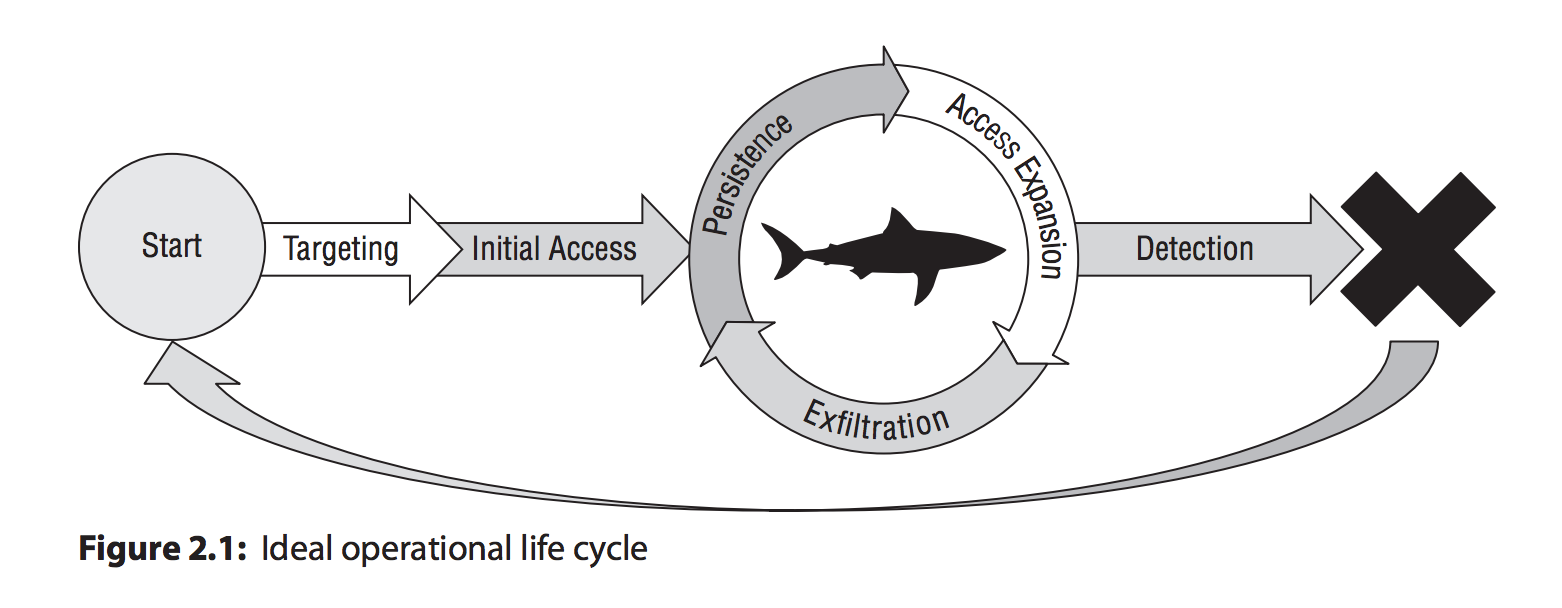

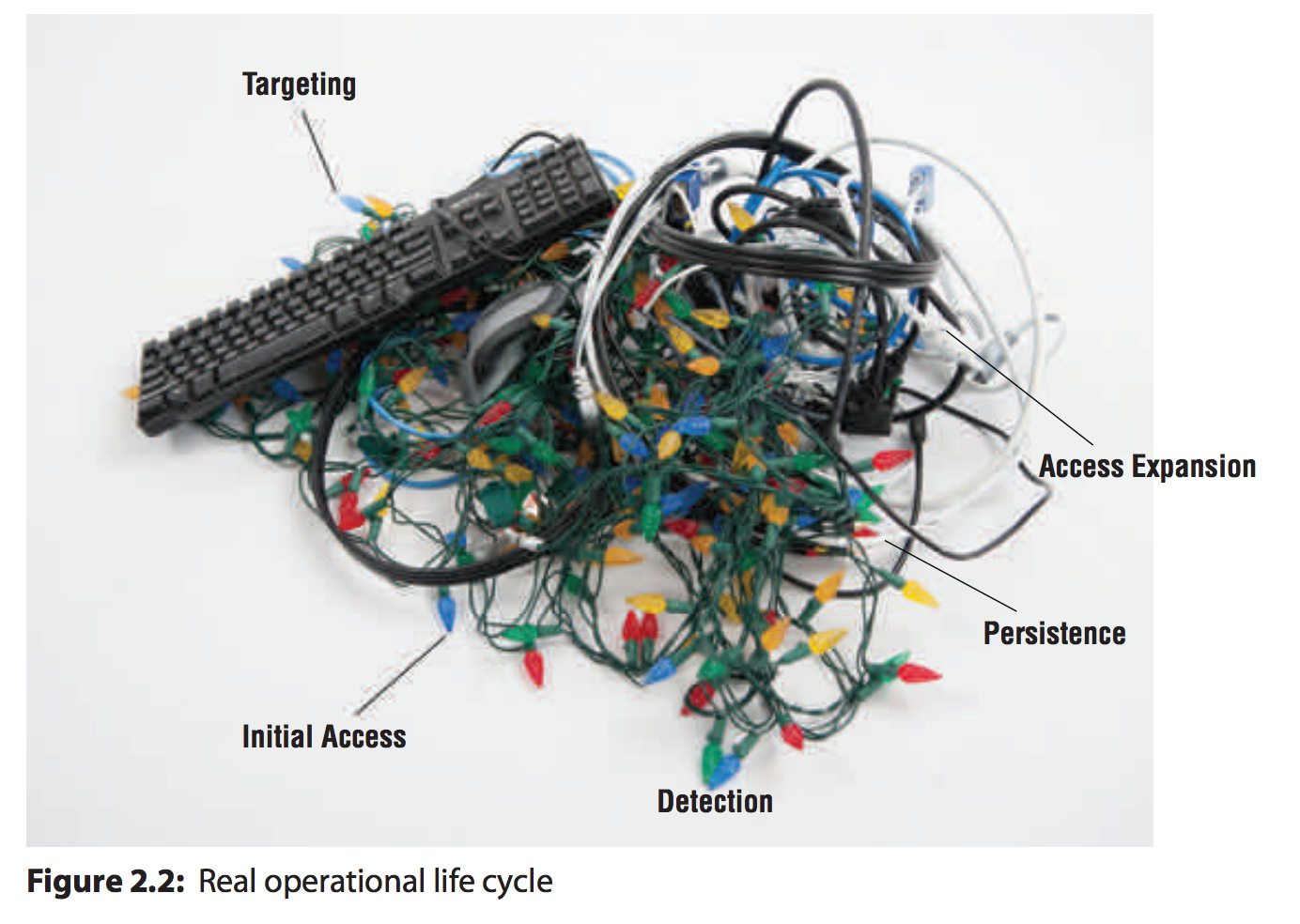

¶ Attack paths & vectors

¶ Attack Surfaces

Attack surfaces encompass all possible avenues through which an attacker can exploit vulnerabilities within a system or network. These vulnerabilities can exist at various layers, including hardware, software, networks, and human factors. Identifying and understanding attack surfaces is essential for assessing and mitigating potential risks effectively.

¶ Attack Vectors

An attack vector refers to the pathway or method used by an attacker to gain unauthorized access to a system or network. These pathways exploit vulnerabilities in the system's defenses, allowing attackers to compromise its integrity, confidentiality, or availability.

¶ Attack Paths

Once an attacker identifies an entry point through an attack vector, they navigate through the system using attack paths. Attack paths depict the sequence of steps an attacker takes to achieve their objectives within a network or system. These paths can involve multiple stages, each exploiting different vulnerabilities or weaknesses. Attack paths are not always linear and may branch out as attackers adapt their strategies to bypass security measures.

Consider a hypothetical scenario: An attacker gains access to a corporate network through a phishing email. From there, they escalate privileges, move laterally through the network, and exfiltrate sensitive data. Each step in this process represents an attack path, highlighting the interconnected nature of cyber threats and the importance of holistic defense strategies.

¶ References

¶ Reference Framework

- coming soon…..

¶ Threat Taxonomies

- A Taxonomy of Operational Cyber Security Risks Version 2 https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/library/asset-view.cfm?assetid=91013

- https://csiac.dtic.mil/articles/evaluation-of-comprehensive-taxonomies-for-information-technology-threats/

- enisa-threat-landscape-2024 /enisa-threat-landscape-2024.pdf

- ENISA Threat Landscape 2024 | ENISA (2023) Foresight Cybersecurity Threats For 2030 - Update 2024: Extended report | ENISA

- ENISA CYBERSECURITY THREAT LANDSCAPE METHODOLOGY (2022)

- https://crfsecure.org/research/crf-threat-taxonomy/ /crf-threat-taxonomy-v2024.pdf (was Open Threat Taxonomy)

- Evaluation of Comprehensive Taxonomies for Information Technology Threats - Steven Launius 2018 - /38360.pdf

- https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/view-all-content/threats

¶ Just Good Enough Risk Rating (JGERR)

from https://brookschoenfield.com/?p=273

Originally conceived when I was at Cisco, Just Good Enough Risk Rating (JGERR) is a lightweight risk rating approach that attempts to solve some of the problems articulated by Jack Jones’ Factor Analysis Of Information Risk (FAIR). FAIR is a “real” methodology; JGERR might be said to be FAIR’s “poor cousin”.

FAIR, while relatively straightforward, requires some study. Vinay Bansal and I needed something that could be taught in a short time and applied to the sorts of risk assessment moments that regularly occur when assessing a system to uncover the risk posture and to produced a threat model.

Our security architects at Cisco were (probably still are?) very busy people who have to make a series of fast risk ratings during each assessment. A busy architect might have to assess more than one system in a day. That meant that whatever approach we developed had to be fast and easily understandable.

Vinay and I were building on Catherine Nelson and Rakesh Bharania’s Rapid Risk spreadsheet. But it had arithmetic problems as well as did not have a clear separation of risk impact from those terms that will substitute for probability in a risk rating calculation. We had collected hundreds of Rapid Risk scores and we were dissatisfied with the collected results.

Vinay and I developed a new spreadsheet and a new scoring method which actively followed FAIR’s example by separating out terms that need to be thought of (and calculated) separately. Just Good Enough Risk Rating (JGERR) was born. This was about 2008, if I recall correctly?

In 2010, when I was on the steering committee for the SANS What Works in Security Architecture Summits (they are no longer offering these), one of Alan Paller’s ideas was to write a series of short works explaining successful security treatments for common problems. The concept was to model these on the short diagnostic and treatment booklets used by medical doctors to inform each other of standard approaches and techniques.

Michele Guel, Vinay, and myself wrote a few of these as the first offerings. The works were to be peer-reviewed by qualified security architects, which all of our early attempts were. The first “Smart Guide” was published to coincide with a Summit held in September of 2011. However, SANS Institute has apparently cancelled not only the Summit series, but also the Smart Guide idea. None of the guides seem to have been posted to the SANS online library.

Over the years, I’ve presented JGERR at various conferences and it is the basis for Chapter 4 of Securing Systems. Cisco has by now, collected hundreds of JGERR scores. I spoke to a Director who oversaw that programme a year or so ago, and she said that JGERR is still in use. I know that several companies have considered and/or adapted JGERR for their use.

Still, the JGERR Smart Guide was never published. I’ve been asked for a copy many times over the years. So, I’m making JGERR available from here at brookschoenfield.com should anyone continue to have interest.

¶ Misc

- https://www.threatmodelingmanifesto.org/

- https://github.com/hysnsec/awesome-threat-modelling

- https://www.threatmodelingconnect.com/

- https://www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed-martin/rms/documents/cyber/

- LM-White-Paper-Threat-Driven-Approach.pdf (/lm-white-paper-threat-driven-approach.pdf)

- LM-White-Paper-Intel-Driven-Defense.pdf (/lm-white-paper-intel-driven-defense.pdf)

- LM-White-Paper-Defendable-Architectures.pdf (/lm-white-paper-defendable-architectures.pdf)

- https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/threat-modeling-12-available-methods/

- https://www.philvenables.com/post/attack-surface-management

- The Attack Path Management Manifesto

- Brook Schoenfield’s Threat Modeling Methods. Much of this method white paper is taken from Securing Systems, Secrets Of A Cyber Security Architect, and Brook’s conference presentations and classes.

- Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS)

- https://www.schneier.com/academic/archives/1999/12/attack_trees.html

- https://www.csa.gov.sg/docs/default-source/csa/documents/legislation_supplementary_references/guide-to-cyber-threat-modelling.pdf (/guide-to-cyber-threat-modelling.pdf)

- How to approach threat modeling (AWS Security Blog )

- Open Information Security Risk Universe https://oisru.org/

- A Threat Modeling Field Guide https://shellsharks.com/threat-modeling

- https://medium.com/nationwide-technology/how-to-perform-systemic-threat-modelling-an-example-a4f875ad72db

- https://medium.com/nationwide-technology/threat-modelling-for-securing-complex-systems-a-step-by-step-guide-87dc248c8c08

- https://medium.com/nationwide-technology/threat-modelling-journey-developing-a-centralised-enterprise-capability-1f120a5fb7ff

- https://notsosecure.com/security-architecture-review-cloud-native-environment

- https://docs.foreseeti.com/docs/simulation-report

- https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/view-all-content/threats

- Annual Cyber Threat Report 2023-2024 (pdf)

- https://safecode.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SAFECode_TPC_Whitepaper.pdf (pdf)

- Cognitive Attack Taxonomy (CAT)

- https://cognitiveattacktaxonomy.org/index.php/Main_Page

- https://cognitiveattacktaxonomy.org/index.php/Main_Page#Introduction_to_the_Cognitive_Attack_Taxonomy_(CAT)

- https://www.cognitivesecurity.institute/

¶ The Art of Threat Modelling (Gartner)

1 November 2023 - ID G00796906 - 47 min read

By: William Dupre

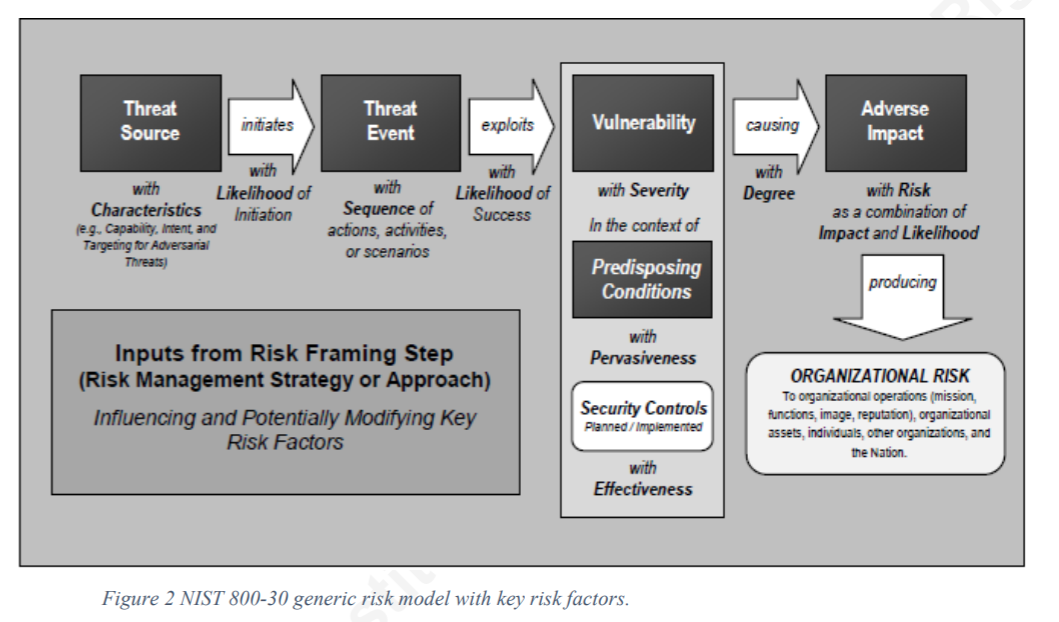

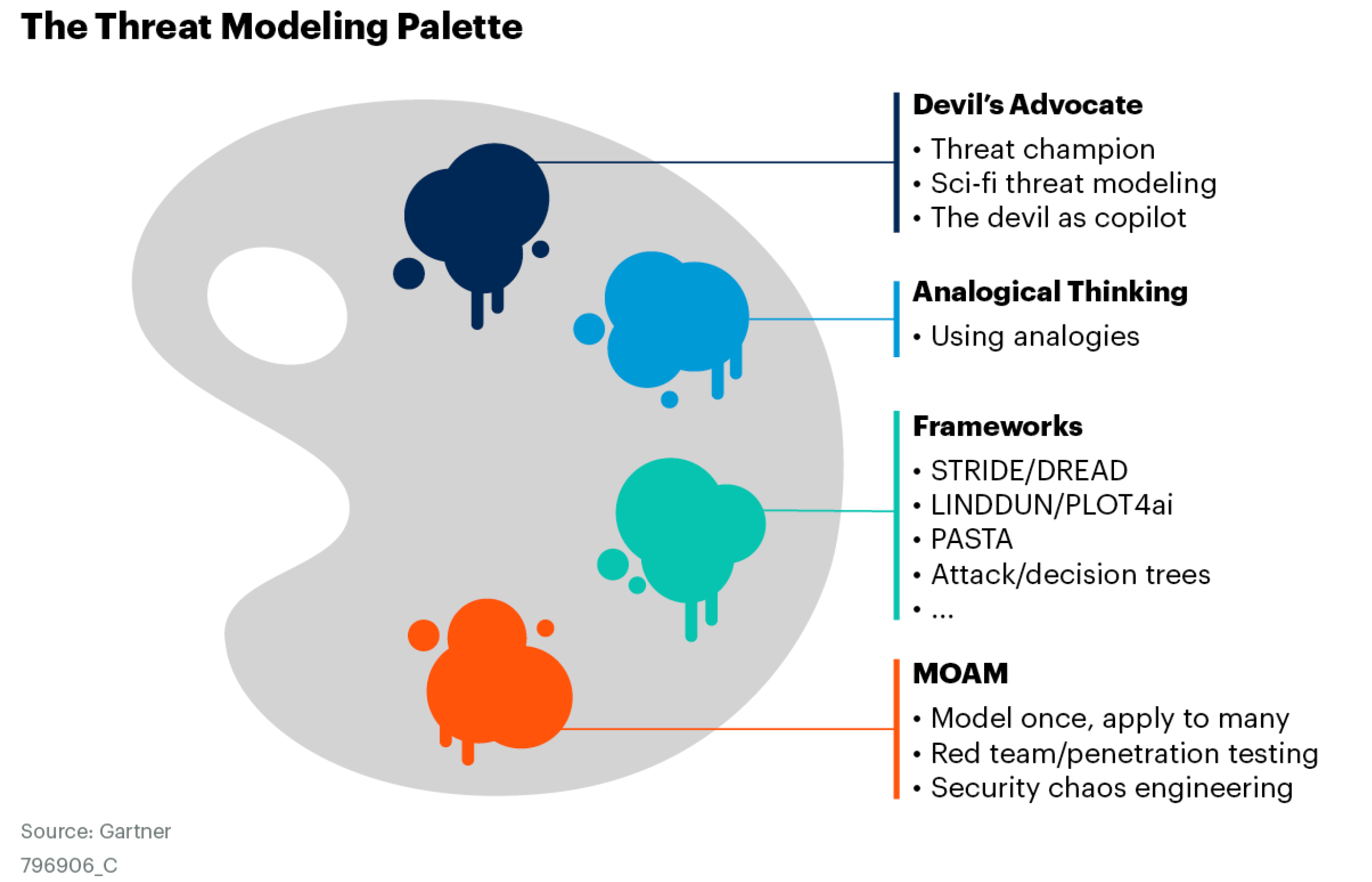

Threat modelling is a form of risk assessment used to identify exposures and mitigations in a system. Security and risk management technical professionals need to use various techniques to instil a threat modelling mindset in their organizations.

¶ Overview

Key Findings

- Organizations struggle to understand security threats that could impact their systems, resulting in limited quality or lack of controls.

- Threat modeling can be a time-intensive exercise because teams need to acquire advanced skills, especially when creating new models from scratch. This leads to a deficit of security requirements and practices within teams.

- Many organizations default to using popular threat modeling frameworks (e.g., STRIDE), failing to take advantage of the diversity of frameworks and techniques available.

- Threat modeling is typically seen as an application security tool or process, leading delivery teams to dismiss it as “the security team’s job.” Also, organizations are not taking advantage of the threat modeling approaches in other areas of digital risk

Recommendations

To better understand threats, security and risk management technical professionals must:

- Use threat modeling frameworks as a basis for understanding threats within a system and to increase the quality and efficacy of implemented controls.

- Use a diversity of frameworks and techniques to get a more complete picture of threats against all digital systems throughout the organization.

- Provide teams with architectural standards and policies based upon threat modeling results.

- Enable teams to do threat modeling by providing automated solutions and a diversity of techniques.

- Instill a threat-conscious mindset by adopting threat modeling across the organization and having multiple roles involved in threat modeling processes.

¶ Analysis

Threat modeling is an architecture-level process for reviewing a system design, enumerating threats and mitigations, validating controls and mapping out the attack surface of a system. This can be for an application, a network, a device, containers, or any system or element of software or hardware. It is a core part of the secure-by-design approach to system development.

While the definition above expresses a formal approach to threat modeling, the goal of this research is to add a bit of art to the formal technique. A general starting point for threat modeling comes from the Threat Modeling Manifesto and centers around four key questions:

- What are we working on?

- What could go wrong?

- What are we going to do about it?

- Did we do a good job?

The key lesson to be learned from these questions is that organizations need to go beyond adopting threat modeling tools and processes for cybersecurity and instill a certain mindset in their employees. In this way, employees will be more threat conscious and can use better judgment with respect to cyber activities. It is an important trait in a world where common threats persist because they consistently work and new threats emerge to adapt to new technologies and sociotechnical structures (for example, threats to and from generative AI [GenAI]). Just relying on formal processes and structures to address these threats will only add friction to threat discovery and anxiety to those needing to understand the threats.

This research will explore a palette of approaches to threat modeling, including both formal and informal approaches, to ensure teams feel like they are threat aware and not just working through a process. Figure 1 provides a sampling of the techniques that will be elaborated on in this research.

Software manufacturers should perform a risk assessment to identify and enumerate prevalent cyberthreats to critical systems, and then include protections in product blueprints that account for the evolving cyberthreat landscape.

— Shifting the Balance of Cybersecurity Risk: Principles and Approaches for Security-by-Design and-Default

Use Common Frameworks as a Basis for Threat Modelling

Organizations should look to formal methodologies for threat modelling to form the basis of an overall program. Using the questions from the manifesto, a process for threat modeling using some common frameworks can be laid out. The following sections will provide guidance on addressing each of the questions.

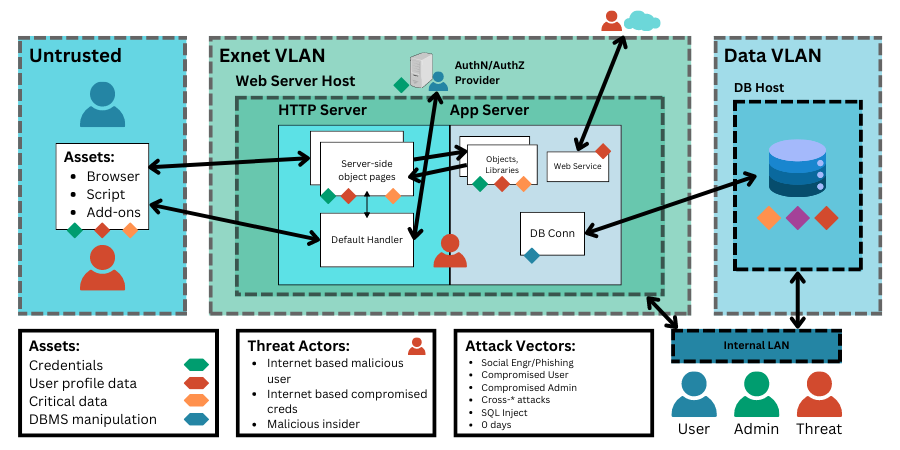

What Are We Working On?

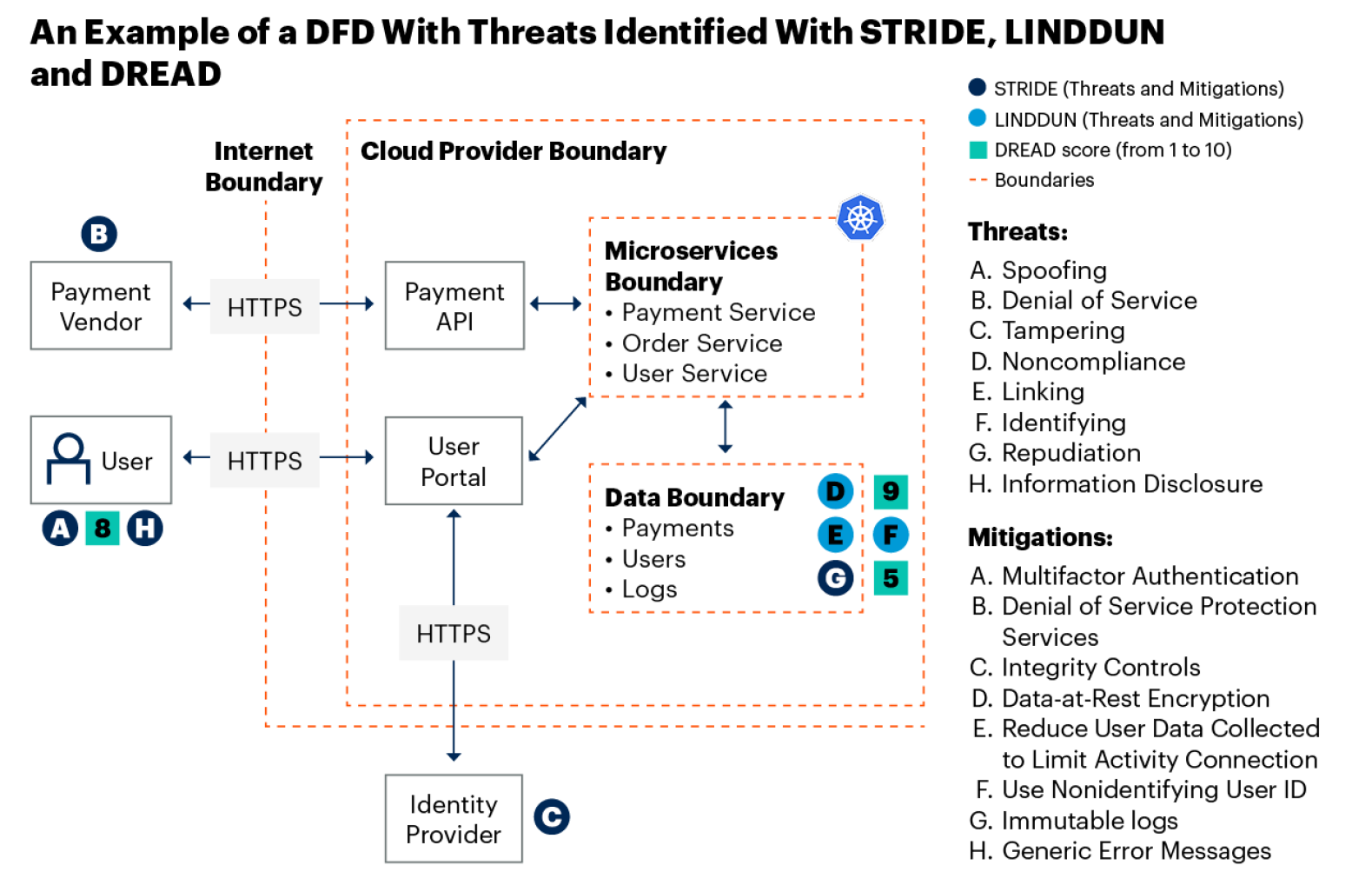

The first step in the process is to get a mental model of the system in question. One approach that is typically used when modeling threats (especially when using standard frameworks) is to create a conceptual view of the system with a data flow diagram (DFD). A DFD can be constructed in different ways, but the primary approach is to model a system using entities within a system, the relationships between those entities and the trust boundaries around the entities. The boundaries represent segments that divide different areas of trust. These could include the internet boundary, a network segmentation or anywhere a trust relationship changes. See Figure 2 for an example of a DFD.

What Could Go Wrong?

Using the DFD created above and a framework (or frameworks) like those discussed below, teams can now identify where threats could impact the system. Some organizations start modeling threats by doing this informally on a whiteboard or printed out diagram. Others may use threat cards illustrating specific threats (see below for card games). As the process matures, automated tooling will be used to identify threats within a system. See the sections below for different frameworks and vendors providing threat modeling tools.

To enhance this part of the process, security teams should bring in threat intelligence to better understand what threats may be feasible. The goal would be to use threat intelligence that is a combination of generic information and information specific to the organization and/or industry to improve the modelling process.

What Are We Going to Do About It?

The primary goal of threat modeling is to address any exposures in a system that could be exploited by threats. At this point, teams should be looking to identify controls that are needed to address those exposures. These could be technical controls (for example, a web application firewall or identity and access management controls), process controls or cultural changes. This process could be manual as well, but tools are available to identify controls.

Using a risk-based approach for this effort is important. Not all threats identified in a threat model have the same risk, and organizations should prioritize mitigations based upon risk appetite. This is a point where threat intelligence will be important as well. Security teams can contextualize threats based upon their own intelligence gathering efforts.

Within the context of risk and threat intelligence, teams can then determine what actions to take. Typical actions fall into four categories

- Eliminate or avoid: If the threat doesn’t exist, there is no risk from it. This may require changing the design or implementation of a system to remove the possibility of a threat. For example, if sensitive data that is being collected could expose the organization to an information disclosure threat, but provides no business or strategic value, then the system should be redesigned to not collect that kind of data.

- Mitigate: This approach requires the identification and addition of controls to detect and/or prevent attacks to an acceptable level. For example, if sensitive data with business value is at risk from an information disclosure threat, then identity and access management (IAM) or encryption controls may need to be put in place.

- Accept: All organizations have to deal with some level of risk — it is necessary to do business. Accepting the risk posed by a threat may be the most appropriate approach due to the complexity and/or cost of either eliminating or mitigating the threat. However, acceptance must be documented and done with full knowledge of stakeholders and reviewed periodically as the threat landscape evolves. Accepting a threat doesn’t mean ignoring it.

- Transfer: This is the process where an organization shifts the consequences (for example, financial) of a risk to some other party. This can be done through an insurance policy so that an organization can recover costs incurred from an incident.

Beyond just applying mitigation measures to the specific system that has gone through threat modeling, organizations should consider those actions as possible architectural or organizational standards that could apply to systems with similar architectures and threat postures. This will provide development and security teams with standards to build secure systems without having to perform a repetitive modeling process.

Did We Do a Good Job?

A key tenet of any process should be continuous improvement. Threat modeling is no exception. Teams should look over the process and determine what changes could be made to a specific threat model or the practice in general. For instance, they could determine that automation is needed to improve the efficiency of the threat modeling process.

When reviewing the process to determine areas of improvement, organizations should consider other aspects of systems that could be modeled. Examples could include illustrating data or system classifications in the model, providing visibility into regulatory concerns that impact threat risk, and modeling insider risk. It is also important to think about what other organizational roles could contribute to the understanding of threats and risk.

An important component of the overall process is documentation at every step. DFDs help to illustrate a system, but keeping track of threats and mitigations will be just as important. These artifacts can provide a current snapshot of system security, drive its evolution, and offer architectural guidance on threat mitigations. This can start with traditional systems such as wikis, file shares and ticket tracking systems, but threat modeling tools will make this effort more efficient, especially if they integrate with chat and tracking systems (for example, Salesforce’s Slack, Microsoft Teams and Atlassian’s Jira Software).

Figure 2 illustrates a DFD with threats identified using various frameworks. Those frameworks are discussed in the sections below.

STRIDE

STRIDE is the most popular threat modeling framework. Gartner clients showing interest in threat modeling typically ask about (and use) STRIDE. The name is a mnemonic that stands for the following:

- Spoofing: An attacker attempts to impersonate an entity (for example, a user, a service) that interacts with some part of the system.

- Tampering: An attacker tries to modify data to manipulate some outcome.

- Repudiation: A user is able to deny actions, leading to a lack of attribution.

- Information disclosure: A system exposes information not intended to be released or that can be used for malicious purposes.

- Denial of service: Normal access to a system is restricted or prevented.

- Elevation of privilege: Permissions or authorizations not available to an entity are granted.

To model threats using STRIDE, teams start with a DFD, then use the threat mnemonic to determine where in the architecture a system could have exposures. For example, a client system that interacts with an API could be spoofed by an attacker causing a data leakage or breach. Another example would be to illustrate where an attacker could possibly elevate privileges to an administrative user if multifactor authentication is not in place. This process would continue across the DFD using all the STRIDE threats. The end goal would be to identify necessary security controls needed for the architecture.

The STRIDE card game called the Elevation of Privilege Game provides an easy way to identify various threats in a system. It can also be used to gamify the process and educate teams on security threats.

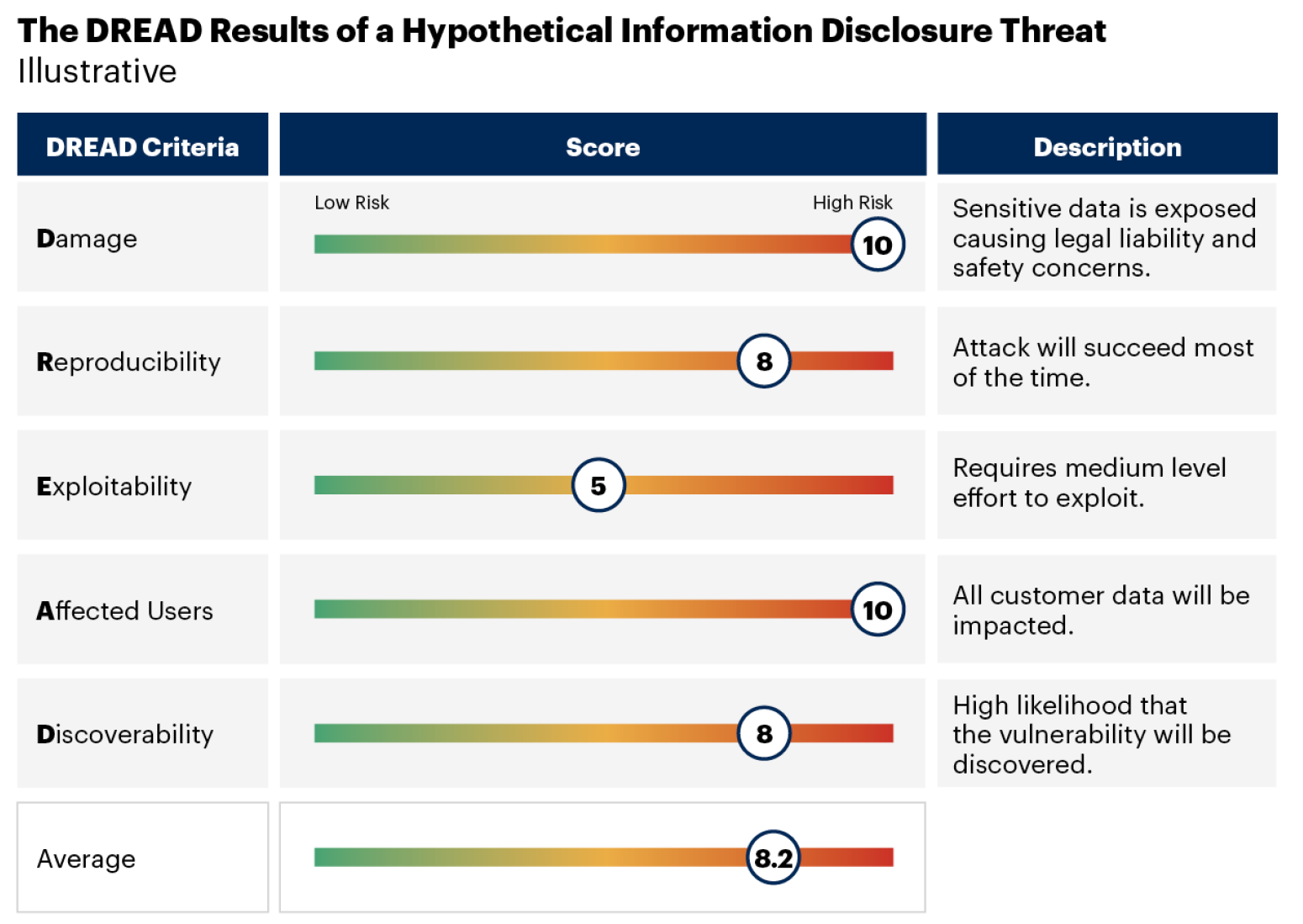

DREAD

DREAD is a risk assessment model that can also be used to complement STRIDE (or other threat models) to help an organization understand the impacts of threats. “DREAD” is an acronym that describes five criteria to help assess threats. These criteria are:

- Damage: How bad would an attack be?

- Reproducibility: How easy is it to reproduce the attack?

- Exploitability: How much work does it take to launch the attack?

- Affected users: How many people will be impacted?

- Discoverability: How easy is it to discover the threat?

Each of these criteria can be scored with a rating from 1 to 10, with the average across all being the overall score for the threat. Figure 3 illustrates the DREAD rating and overall score of a hypothetical information disclosure threat.

DREAD should be used when a rough idea of risk is needed to help prioritization efforts. Organizations should consider using DREAD along with other models.

LINDDUN

Security and risk management technical professionals use the confidentiality, integrity and availability (CIA) triad to align controls to information security risks. While the confidentiality component of the triad is about protecting data against unauthorized access, it lacks the focus of protecting the rights of individual people in controlling their personal information. That is the domain of privacy.

Privacy regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), are proliferating around the world. These are efforts by governments to provide citizens with better control and protection of their personal data. In general, these regulations have the privacy protection goals of unlinkability (personal data cannot be linked across domains), intervenability (individuals have control over the processing of their personal data) and transparency (data processing of personal information can be understood and reconstructed at any time). Security professionals should see these goals as a complement to the CIA triad and align their controls to them when data privacy is a concern.

Organizations that have concerns about data privacy should include a more focused threat modeling approach. One such framework is LINDDUN which provides a catalog of privacy threats to enable the investigation of a wide range of design issues that could impact privacy. The acronym “LINDDUN” represents the following privacy threat types:

- Linking: ability to associate data or actions to an individual ■ or group.

- Identifying: learning the identity of an individual.

- Nonrepudiation: being able to attribute a claim to an individual.

- Detecting: deducing the involvement of an individual by observing.

- Data disclosure: excessively collecting, storing, processing or sharing personal data.

- Unawareness: insufficiently informing, involving or empowering individuals in the processing of personal data.

- Noncompliance: deviation from security and data management best practices, standards and legislation.

The methodology consists of modeling a system (using a DFD), eliciting threats (using a mapping table and threat trees) and managing threats (prioritizing and mitigating identified exposures).

When modeling threats with LINDDUN, it is important to consider the roles involved in the process. Legal and compliance teams should take part in the effort to better inform the organization of the legal and regulatory aspects of privacy. Security and IT teams should also be involved to make sure the necessary technical protections can be put in place.

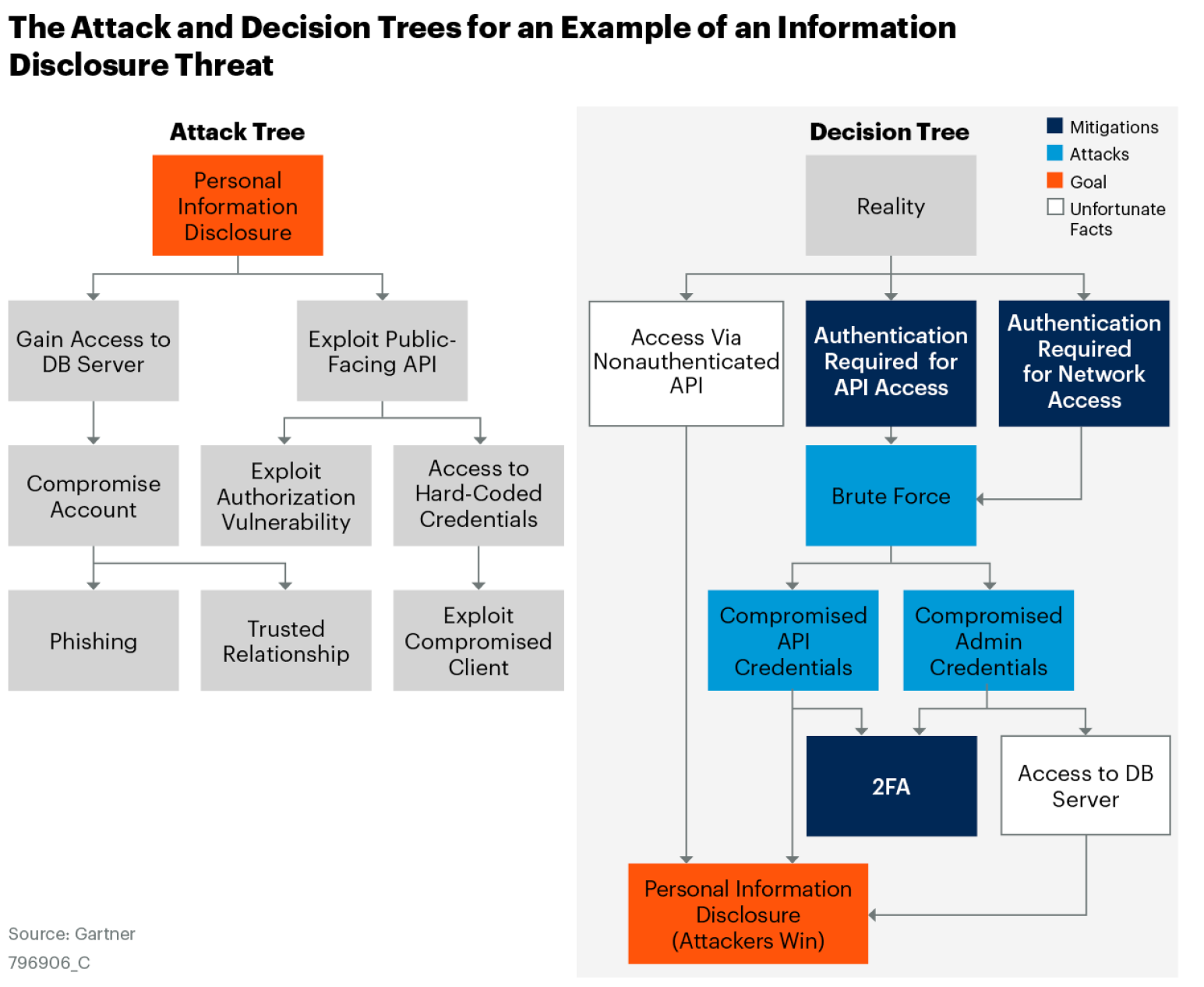

Attack Trees and Decision Trees

Attack trees are an attacker-centric threat modeling technique that allows teams to model how an attack might unfold. The attack scenario is modeled as a tree structure with the root node being the goal of the attack and leaf nodes being approaches for achieving that goal. Unlike other threat modeling frameworks, attack trees do not use a DFD.

An alternative to attack trees is a decision tree which models the actions an attacker might take at each stage of an attack and what a system can do to counter the attacker. This approach can help teams understand the attacker mindset and decision-making process, along with the return on investment (ROI) of their attack.

Attack and decision trees can be used as a stand-alone approach or as a further analysis complementary to other types of threat modeling techniques. For instance, once a threat is defined using STRIDE, an attack or decision tree can be created to illustrate the attack sequence of that possible threat. The process could be further enhanced with adversary tactics and techniques as defined by the MITRE ATT&CK framework or the Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain framework. See Figure 4 for examples of attack and decision trees.

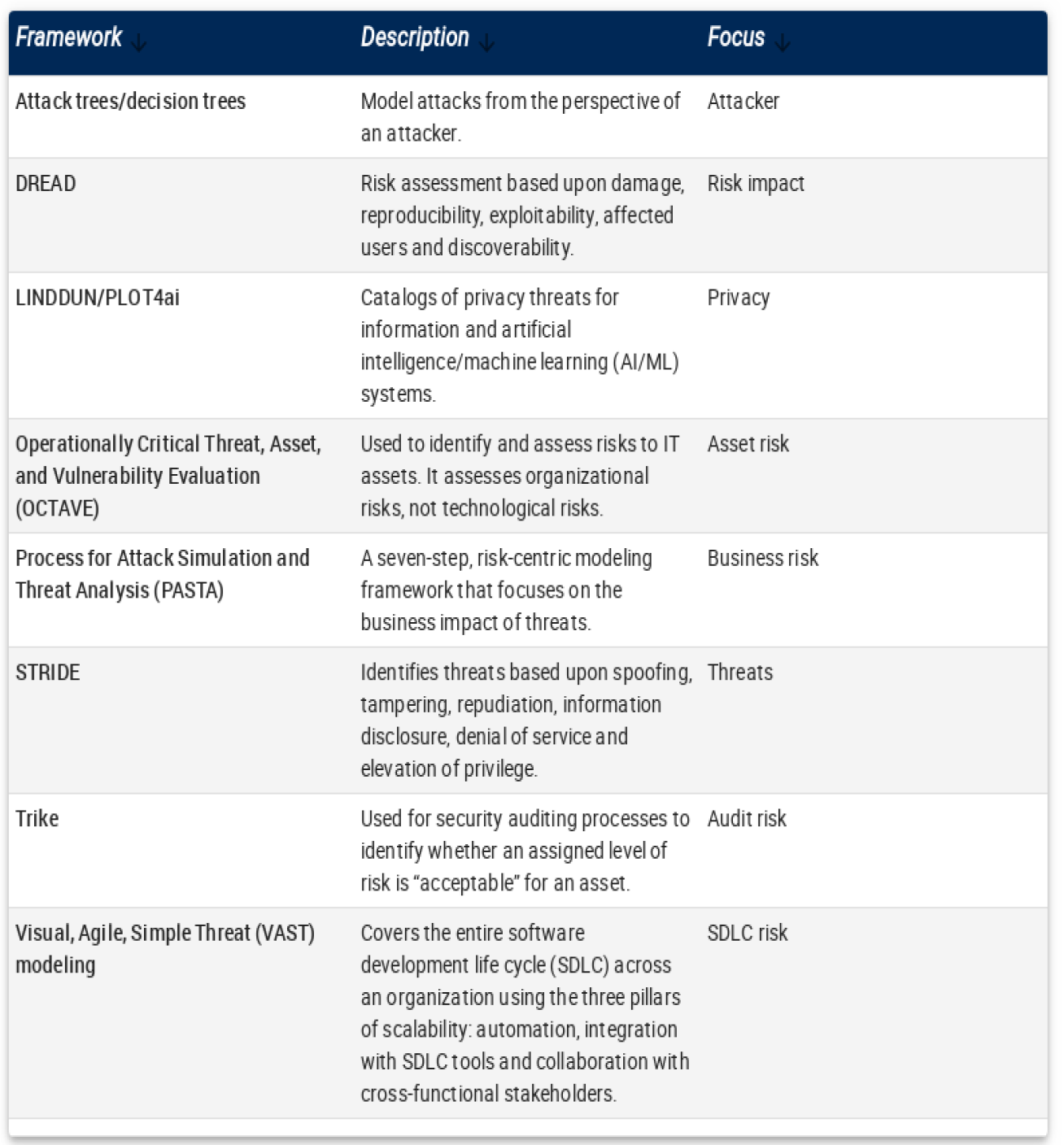

Others

The above modeling frameworks and techniques are popular, but don’t constitute an exhaustive list. Table 1 lists the frameworks mentioned above along with others that are available.

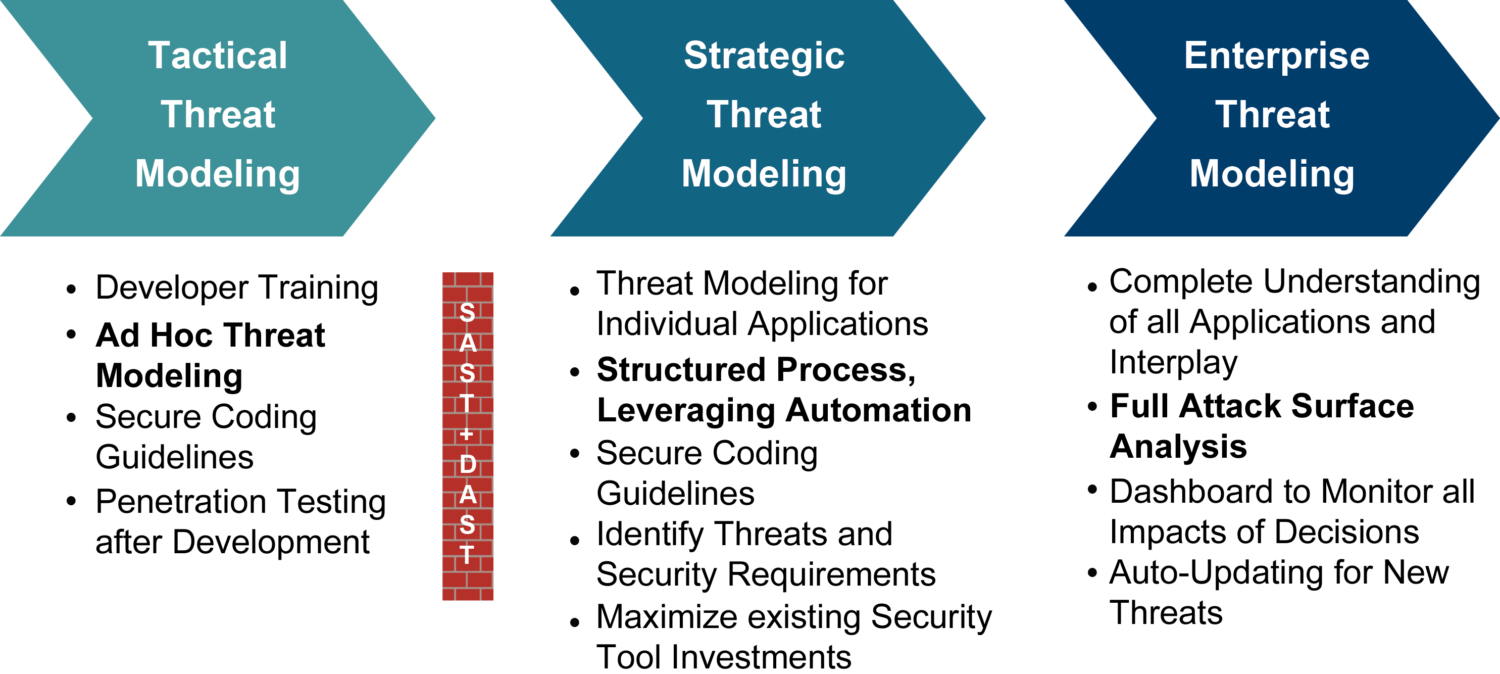

When to Conduct Threat Modeling With Frameworks and With Whom

Organizations should use these frameworks at selective points within risk assessment processes to get a broad and consistent understanding of threats. These points should align with the different phases of system evolution, such as:

- Initial system design: When a new system is being designed, performing threat modeling in the early stages, before coding starts, will be important in verifying the design and driving architecture standards and requirements for development.

- Legacy system reviews: In this context, a legacy system is one that was developed and put into operation before threat modeling was conducted. Even in this case, organizations should look to create an architecture view of the system and perform threat modeling on the system. It may be more difficult or costly to apply controls in this case, but it is crucial that threats to legacy systems are understood and mitigated where possible. This effort should not be considered an all-or-nothing effort. Modeling an entire production system may be a herculean task, so it may only be feasible to model certain aspects of a system or the entire system but at a more reasonable abstraction level.

- Tactical architectural updates: No system stays static over time; they all evolve. Threat modeling done at one point will lose its relevance quickly as new development proceeds. However, this does not mean that teams must perform threat modeling for every small change to a system. But one threat modeling process should be done when significant changes are being made. What is significant? There is an art to that as well. Examples could include moving from containers to serverless deployments, implementing changes to regulations (the GDPR, the CCPA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPAA], etc.), changing from web to mobile clients, using third-party APIs, moving from on-premises to SaaS solutions for corporate applications, and installing Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

- Strategic IT or business changes: Digital transformation is constantly occurring and, sometimes, organizations need to make significant decisions on their IT strategies. In these cases, threat modeling should be a key aspect of a digital transformation risk assessment. For instance, if a strategic decision has been made to move all applications from an on-premises data center to cloud-native deployments, then planning should include threat modeling. Also, threat modeling should be done when exploring new business opportunities, like entering a new regional market or during a merger and acquisition process.

- Incident postmortems: After a security incident, security teams, along with relevant stakeholders, should review the system’s threat model to determine if new controls are needed. If a threat model doesn’t exist for a system, this may be the perfect opportunity to rectify that deficiency.

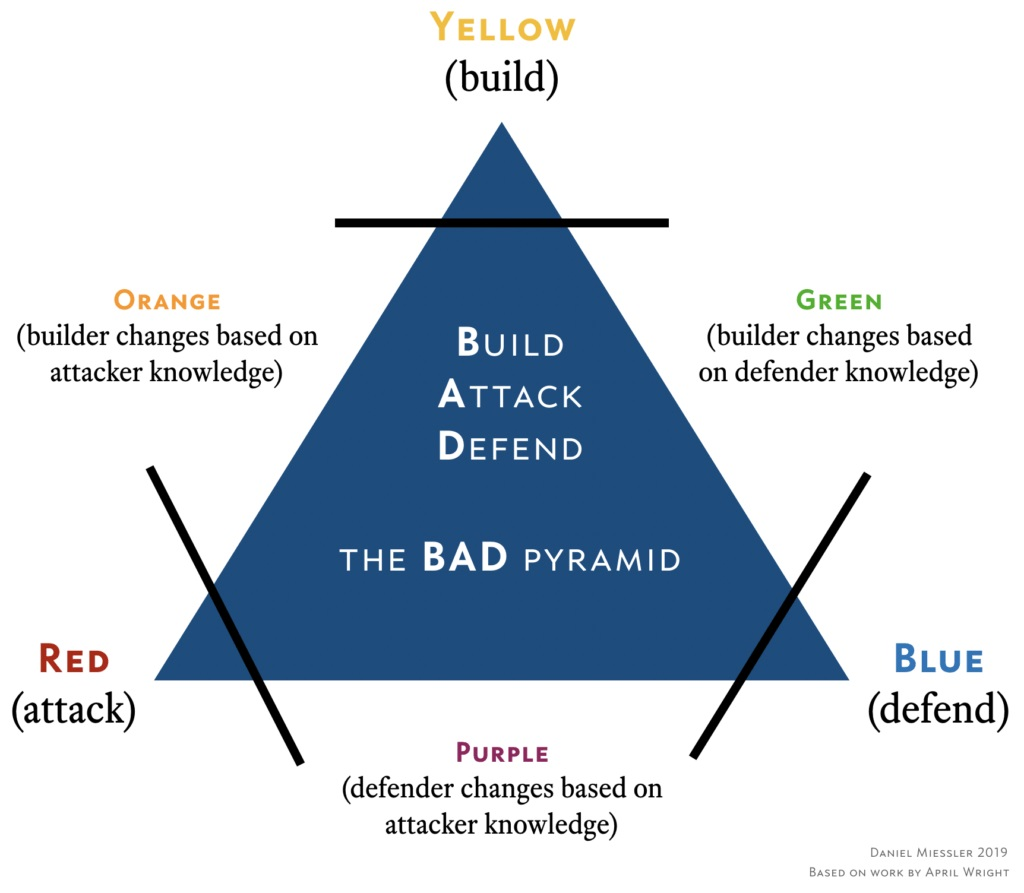

It is important that a diversity of roles within the organization are involved in these exercises so that a complete picture of the threat landscape can be illustrated. For instance, business roles help provide context to what is being modeled, while security roles provide guidance on how a threat could unfold. Architects and developers will also provide insights into components of the application and infrastructure.

Getting a diversity of roles to participate in this time-consuming effort can be a challenge, though. This is where security teams need to express the benefits of such approaches by having the different roles understand how their specific knowledge helps put threats in context and provide guidance on mitigation options. What’s in it for them are more secure products, less rework on bolt-on security and a better secure-by-design approach to system development.

If an organization has a security champions program, then it should look to those roles to help with the threat modeling process.

Challenges and Benefits of Using Threat Modeling Frameworks

Using threat modeling frameworks should be a core part of a risk assessment process. Organizations should determine which framework is appropriate for a particular system based upon what they are trying to target — risk, understanding threats and/or privacy.

One challenge of using these frameworks is that they can be a labor-intensive exercise for many organizations. However, such activities can provide a shared learning experience for teams. There are also ways to gamify these efforts to address the possible boredom that could arise. For example, the Elevation of Privilege Game, LINDDUN GO, and OWASP Cornucopia are card games that help create a more collaborative and enjoyable environment for teams.

Even with gamification, however, manually performing threat modeling using these frameworks can be an expensive endeavor. To reduce the costs, organizations can look to tools that can automate the effort. Vendors in this space include IriusRisk, Security Compass and ThreatModeler. Other solutions include Computer Aided Integration of Requirements and Information Security (CAIRIS), Microsoft Threat Modeling Tool, OWASP Threat Dragon and Threagile.

In general, identifying threats to a system helps organizations plan and implement security controls, and enable a more threat-conscious mindset. The additional benefits of using the above frameworks include:

- Structuring the practice: Teams have a place to start with threat modeling using a common framework and library of threats to guide the practice. This helps improve the consistency and repeatability of threat modeling across the organization.

- Providing enterprise architecture standards: Mitigations and controls identified during the threat modeling process should provide guidance for other systems and architectures in the organization. For example, if an application is vulnerable to a spoofing attack because it lacks multifactor authentication (MFA), then it might be appropriate to make MFA the standard for all applications with similar characteristics. This will provide teams with standards for a secure-by-design or “paved path” approach to application development.

- Experimenting with prospective architectures: A threat model allows teams to test ideas regarding architectural approaches to development, whether it is a new system design or an addition to an existing design. For example, if a development team is looking to move from containers to serverless deployments, a threat model can give them insights into the implications and costs of such a change.

- Improving incident response: A threat model can provide valuable information on where a system may be vulnerable. Incident response (IR) teams can use this information as part of an IR exercise to test assumptions about the system. They can also look to the threat model after an incident to get a better understanding of what may have gone wrong. Some threat modeling frameworks may do better at this than others (for example, decision trees).

- Supporting compliance: As more scrutiny of cybersecurity comes from regulatory agencies, threat modeling will become an important component of compliance practices. In April of 2023, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), in partnership with several other agencies and governments, issued guidelines for secure-by-design practices. The agencies “recommend manufacturers use a tailored threat model during the product development stage to address all potential threats to a system and account for each system’s deployment process.” While this is currently just guidance, more forceful approaches could be coming.

- Contextualizing vulnerabilities: Many organizations struggle to prioritize vulnerabilities being reported from their various security tools (for example, application security testing and vulnerability management tools). A threat model can put these vulnerabilities in context. For example, if an application with a high severity vulnerability is being deployed into an environment shown to be vulnerable to threats, then that vulnerability may need higher priority than one being deployed to a more secure location. Teams need a mental model of threats in a system to better triage vulnerabilities and plan remediation.

Use a Diversity of Techniques to Understand Threats

Using frameworks to perform threat modeling is an important component of an organization’s risk assessment process. The frameworks should be used, as a manual effort or along with automated solutions, to understand threats. However, instilling a threat-conscious mindset into the organization will take a diversity of techniques. Some of the techniques are informal, and those, listed below, get to the heart of the art of threat modeling.

The Devil’s Advocate

Threat Champion

Science Fiction Threat Modeling

The Devil as Copilot

¶ Guidance

Security and risk management technical professionals should:

- Use standard frameworks as a basis for understanding threats in a system. Determine the focus of a threat model (threat view, risk, privacy, asset view, etc.) and use an appropriate framework.

- Involve other roles in the threat modeling process. Using frameworks as a start can educate these roles on the threat modeling process, provide insights into the process and help them better understand the big picture of security. Which roles to include first will depend on the specific threats being explored. Bringing in developers and technical architects will be necessary when conducting threat modeling on an application or production system. Including the legal team may be necessary when modeling threats concerning privacy. If performing threat modeling on a cyberphysical system, then including appropriate device and control system experts will be necessary.

- Start using informal techniques (as mentioned in this research) to instill a threat conscious mindset in the organization. Work with security champions to promote these techniques, and also learn new techniques from them.

- Wherever there is digital risk within the organization, use some form of threat modeling to understand the extent of the risk.

- Create architectural standards and policies based upon threat modeling results. Standards could include technical controls such as MFA, API security and/or bot mitigation solutions, and service mesh technology for mutual authentication. Other standards could include policies for handling sensitive data like personally identifiable information (PII) or IP.

- Revisit formal threat models on a regular basis to ensure they stay relevant and that implemented controls are still appropriate.